Extent of Þingvallavatn

Lake Þingvallavatn lies in a rift valley that extends south from the Langjökull glacier to mount Hengill, and from Botnssúlur in the west to Lyngdalsheiði in the east.

Lake Þingvallavatn is the largest natural lake in Iceland, about 84 square kilometres, at an altitude of about 100 metres above sea level. The deepest part of the lake measures 114 metres, which means that it reaches below sea level.

The lake covers an area of 84 square kilometers. It´s catchment area though is way larger, covering 1300 square kilometers.

Þingvellir þjóðgarður / Gagarín

Catchment

The catchment area of Þingvallavatn, about 1300 square kilometres, lies in the same direction as the fissures in the area, and it's layout and functions have been shaped by its geological history.

As the ice cap retreated 10.000 years ago, a glacial river flowed from the Langjökull area and water collected in the Þingvallavatn before flowing onwards to the ocean through the river Sog. This process was halted by the eruptions in Eldborgir and Skjaldbreiður. The latter one blocked the flow of the glacial river, so the majority of the water had to travel underground channels to reach the lake. The Eldborgir eruptions partially blocked the river Sog causing the brown trout to get stuck in the lake.

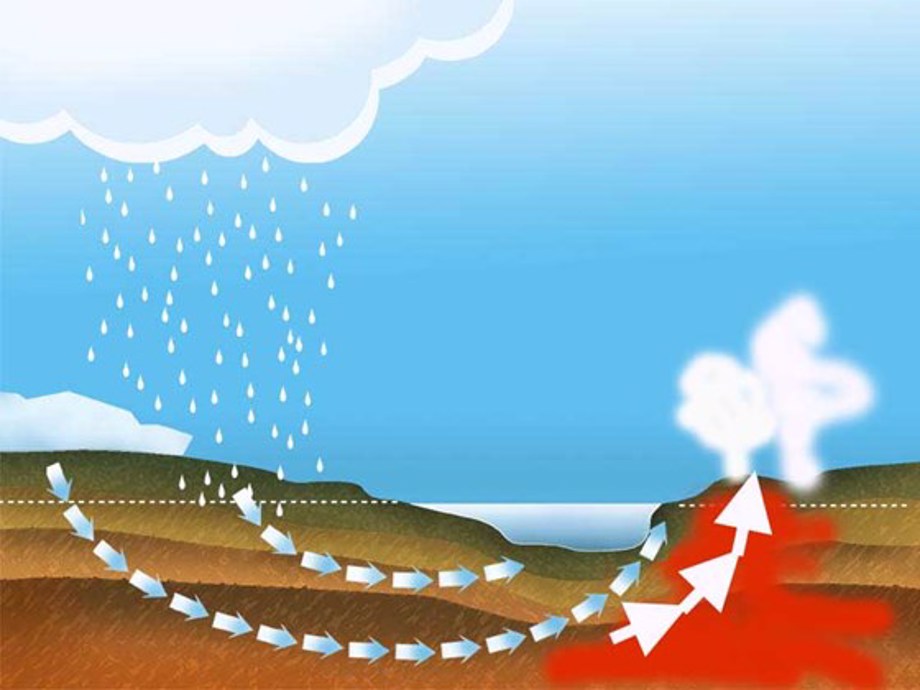

Today, around 90% of the water influx in Þingvallavatn runs along underground channels to the lake. It takes 20-30 years for water to run south into Þingvallavatn from the glacier Langjökull, and it's said that, on its way, it passes through the earth's mantle at a depth of eight kilometres. The rain that falls on the lava takes 2-4 months to enter the lake.

Movement of tectonic plates affects the area, forming rifts and ravines in the landscape. In Flosagjá, water resurfaces and flows to lake Þingvallavatn after it´s travel from Langjökul, 50 km to the north.

Þingvellir National Park / Gagarín

Harnessing the energy

South of Þingvellir is Nesjavellir, the largest high-temperature area in the country. There, water heats up underground by contact with hot rock, and is forced up through the crevices and faults under mount Hengill.

Reykjavík Energy has harnessed the high-temperature area to heat cold water for household heating with low-pressure steam and drillhole water, but it also generates electricity with high-pressure steam.

Part of the water from Langjökull comes out as a cold water in the norhtern part of lake Þingvallavatn. Meanwhile other parts of the water goes further down and comes up at the lakes south end, Nesjavellir, as a steaming hot water.

Þingvellir National Park